I was in Asheville back in April for the North Carolina Writers Network Spring Conference. Zackary Vernon was there teaching a workshop on writing young adult literature. I had met Zack only once before in person, about a month earlier in the Los Angeles International Airport following AWP. But the world is small, especially the world of writers, and I used to work with Zack’s wife, Jessica Martell, when she taught about a decade ago at Lincoln Memorial University. It was fun to spend some time with both of them between conference sessions, and just before I headed home, Zack slipped me with a copy of his novel, Our Bodies Electric.

Our Bodies Electric is a coming-of-age story set on Pawley’s Island, South Carolina. We meet the main character, Josh, when he’s in the sixth grade and follow him into high school and his sexual awakening. Despite the very conservative and religious shadows cast by his parents and community, Josh finds surprising refuge in the words of Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, which gives him the strength to love his body and his desires in all their forms.

Zachary is an Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies at Appalachian State University. He is a co-editor of Summoning the Dead: Essays on Ron Rash, and he is the editor of Ecocriticism and the Future of Southern Studies. His scholarly research and creative nonfiction and short fiction have been published widely. Zack agreed to answer a few questions about his writing, the need to accept differences in people, and his relationship with Walt Whitman.

DL: I think you and I are not too far apart in age, which is based partly on the fact that there was a lot I recognized from my own youth in Our Bodies Electric. How much of your own life and experience factored into setting the time and place for this novel?

ZV: Our Bodies Electric is set in my hometown of Pawleys Island, South Carolina, during the early to mid 1990s. It’s a southern coming-of-age story about a teenager named Josh who struggles against the pressure to conform to social conventions placed on him by his religious family and community, particularly as he enters his teenage years and tries to understand his body and sexuality. Josh hangs out with a bunch of outcast teenagers who get up to all kinds of hijinks, but more importantly they help each other through this period of rapid change and development. They need each other because they don’t get much help from their families or school or church. Those institutions fail them, because they constantly tell young adults that the things they think and do are evil. Some teens end up conforming to conservative conventions, and some decide to break the mold.

I am Josh, or at least Josh is some version of me. All of those details come from my own life and the lives of my friends between the sixth and nineth grades. I think that period might be the one in which we change the most rapidly; there is a fluidity during these years. We go from being kids to being hormonal teenagers who all the sudden possess very adult ideas and desires.

Throughout the novel, Josh sets off on an adventure of experimentation and self-discovery, which is of course natural and healthy. But the puritans surrounding him want nothing more than to police his behavior and stamp out any curiosity they believe is abnormal and thus dangerous. His journey is strange and uncomfortable at times, but hopefully he’s a better and more authentic person at the end of it.

DL: Walt Whitman and Song of Myself play a fairly pivotal role in this novel, and your students report that you really enjoy teaching Whitman. Did you know from the beginning of Our Bodies Electric that Whitman and Song would be part of Josh’s narrative? Or did that come later in the writing process?

ZV: Walt Whitman was a huge inspiration both for the form and the content of the novel. Regarding content, I’ve been a massive fan of Whitman since I first read him in high school. So his ideas have been rattling around in my head for decades. The year that I started earnestly working on Our Bodies Electric was the year I turned 37. And Whitman in “Song of Myself”—or the Whitman-esque persona that narrates the poem—is also 37. The first section contains these lines:

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

So I decided that during my 37th year of life, I would read Whitman every single day. And I didn’t miss a single one. I read various portions of Leaves of Grass for 365 consecutive days. Some days I’d only read a few lines, and some days I’d really dig in. So this year steeped me in Whitman’s language and ideas more than ever, and that happened to also be the time that I was seriously writing the novel.

For the protagonist Josh, Whitman becomes a sort of life coach and an inspiration. Josh reads Whitman and his ideas help him understand and accept himself.

In terms of form, I divided the novel into 52 sections, which are in dialogue with the 52 sections of “Song of Myself.” That’s not to say that there is a one-to-one mirroring going one—i.e. Section 1 of “Song of Myself” is in dialogue with Chapter 1 of my novel. It’s not that similar. But I did borrow the 52-section structure, and I tried to add a Whitman easter egg into every chapter. These are mostly subtle. There are only a handful of passages that actually allude to Whitman directly. But I’d say in a more general sense, Whitman pervades the entire novel.

DL: Besides the fact that the scenes throughout your novel sing all the way through, the thing I love best is how empathetic this book is. Josh is a compassionate character—to others and usually to himself—but you as the author give so much compassion to characters who aren’t compassionate to others. I’m thinking in particular about Josh’s fire and brimstone minister. Is there a person or situation that instilled so much empathy in you as a person and a writer?

ZV: My hope is that the novel has a message about the necessity of accepting difference. I think one could read it as being a harsh critique of Pawleys Island. But it’s not. It’s a critique of the stultifying impulse to conform that is often thrust onto kids and teenagers in conservative, religious communities. This exists everywhere. It’s not unique to Pawleys or even to the South. I taught for a year at a catholic college just north of Boston. The students there felt conflicted about themselves just as much as anyone I’ve ever seen in the South.

My novel is set in Pawleys simply because I happened to be from there; I lived there during those formative years that seem to make us who we are for life.

So I want to be clear too that I’m not making fun of Pawleys Island in any way. The novel is not mean-spirited or tragic. It’s humorous, and if anything it makes a plea to celebrate life. Also, the heroes of the novel come from Pawleys. Yes, the protagonist feels tortured by the conservative community here. But it is also locals who show him that there are different ways of being in the world. In other words, that place, like all places, contains good and bad. Josh doesn’t have to flee to find himself. He does that there, with the help of the many small-town eccentrics he meets along the way.

I was always fascinated by the black sheep I encountered in Pawleys Island. Some of them you could spot easily, but others didn’t look like punks or drifters. Take, for example, my high school English teacher Mary Ginny DuBose.

Miss DuBose was the most transformational teacher I’ve ever had. I’m talking about ever—more than any teacher I had through college or grad school.

She taught us to be independent thinkers. She cued us in to the fact that there was a great big world out there. And in it people thought in ways that were very different from our parents and our church leaders and members of our communities. That’s not to say that local folks were wrong all or even some of the time. But our world was limited in certain ways, and then Miss DuBose came along and started opening doors.

It’s cliché perhaps—very Dead Poets Society—but Miss DuBose expanded our minds. She was a tough teacher, but also very kind. I don’t know how she pulled that off. I’ve been teaching now for nearly two decades, and I’ve never been able to get that balance right—tough enough to prompt and prod even those most reluctant of souls, but kind enough to empathize and inspire.

And crucially it was Miss DuBose who first introduced me to Walt Whitman. Along with Miss DuBose, Whitman gave us permission to be ourselves; or perhaps both of them made us realize that we didn’t need permission in the first place.

DL: I understand you wrote a lot of nonfiction before you turned to fiction. Can you talk about your path to publication, both in general and specifically this novel? How did you come to work with Regal House/Fitzroy Books?

ZV: I’ve wanted to be a writer since high school. I don’t know why exactly. It’s not like I knew any writers personally. Maybe I’d seen writers romanticized in films, or maybe it was my Whitman obsession. But somehow I viewed writers as being subversive, and that’s what I wanted to be.

I was really into music in high school. And I think I was a decent musician, but that never felt like a good fit. Plus I could never write songs. I tried and tried, but it just never came, so at best if I had continued in music, I’d be in some kind of cover band, or playing backup in someone else’s band.

Writing stories and novels, though, was a different matter. When I got to college, I had no problem writing. In fact, I couldn’t stop. I wrote obsessively. That’s not to say the stories I was writing were good. They weren’t. They were terrible. But they flowed out of me. Something was there, some inclination. But I had to read a lot and study for a long time before the stories became halfway decent.

Samuel Johnson said, “The greatest part of a writer’s time is spent in reading, in order to write: a man will turn over half a library to make one book.”

I read voraciously and wrote about a million stories and two novels in college. Again, these were terrible and will never see the light of day. But I was very disciplined, and I produced a lot.

Then after undergrad I desperately wanted to get an MFA, but instead I got a PhD. I foolishly thought that this was the practical way of going about things. I had no idea at that point how bad the academic job market was.

What ended up happening was that for my MA and PhD and then when I got my first two teaching positions, I only wrote scholarship and nothing creative. It was a creative dry spell that lasted for close to a decade and a half. I wrote and published a lot of scholarship during that period, and I love that kind of writing, but it wasn’t what I was most passionate about.

When I got tenure, I decided that I was going to write fiction again. I dropped all my scholarly projects and dove into what would become Our Bodies Electric. The writing came as effortlessly as it did in college, except this time I think it was decent, or at least it was genuinely me. I was no longer trying to be someone I’m not—to write like Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor. I was no longer trying to be pretentious, writing serious historical southern gothic tales. Instead, I wrote humorous stories, and most of them were true in some way—things I’d experienced, things I’d heard about during my childhood and adolescence in Pawleys.

I wrote the novel is a strange roundabout way. I drafted the chapters more like short stories than chapters in a novel. And then I tried to weave together the best ones. And since they were mostly autobiographical, it wasn’t hard to create a coherent overarching narrative.

I got involved with Fitzroy Books, the YA imprint of Regal House Publishing, through my friend and colleague Mark Powell. Mark had read my book and helped me revise it, and he also had a book accepted at Regal House around this time. He recommended the press, saying it was the up-and-coming new indie in the South. So I sent them the book, and they seemed to like it right away.

DL: When we saw each other last, you were teaching a workshop on writing young adult fiction. What’s one of the most important lessons or advice you try to pass on to writers interested in YA fiction?

ZV: I came to YA accidentally. I didn’t write Our Bodies Electric as a YA novel. The main characters were adolescents, but I was imagining it being akin to books like Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms, Carson McCullers’s The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, or Lewis Nordan’s Music of the Swamp. In other words, I thought of the book in this lineage of coming-of-age adult literary fiction. And I hope my novel is that. But I also don’t want it to be merely read by adults.

It was my editor Jaynie Royal who had the idea of marketing the novel as YA. I was resistant at first, but Jaynie ultimately convinced me when she asked who I thought needed to read this book: other middle-aged liberals like me or young adults who might be struggling in the same ways that I struggled. I found and still find that idea very compelling.

In terms of advice for YA writers, I would just say that it’s important to be authentic. Teenagers can smell a phony from a mile away. You can tell about your own experiences or you dream up stories, but make sure they have an emotional or ideological truth to them. We desperately need to be reminded right now of the better angels of our nature—to be understanding and kind, even when people in power aren’t doing so.

I hope that’s what comes across in my book. In it, a small group of teenagers try like hell to discover who they are, even if their real identities go against the established community they live in. They rebel nonetheless, and as a result they learn to live more authentically, to celebrate and sing themselves.

I’m so grateful to Zackary Vernon for answering these questions. If you haven’t already read Our Bodies Electric, be sure to order your copy, available at bookshop.org or wherever books are sold.

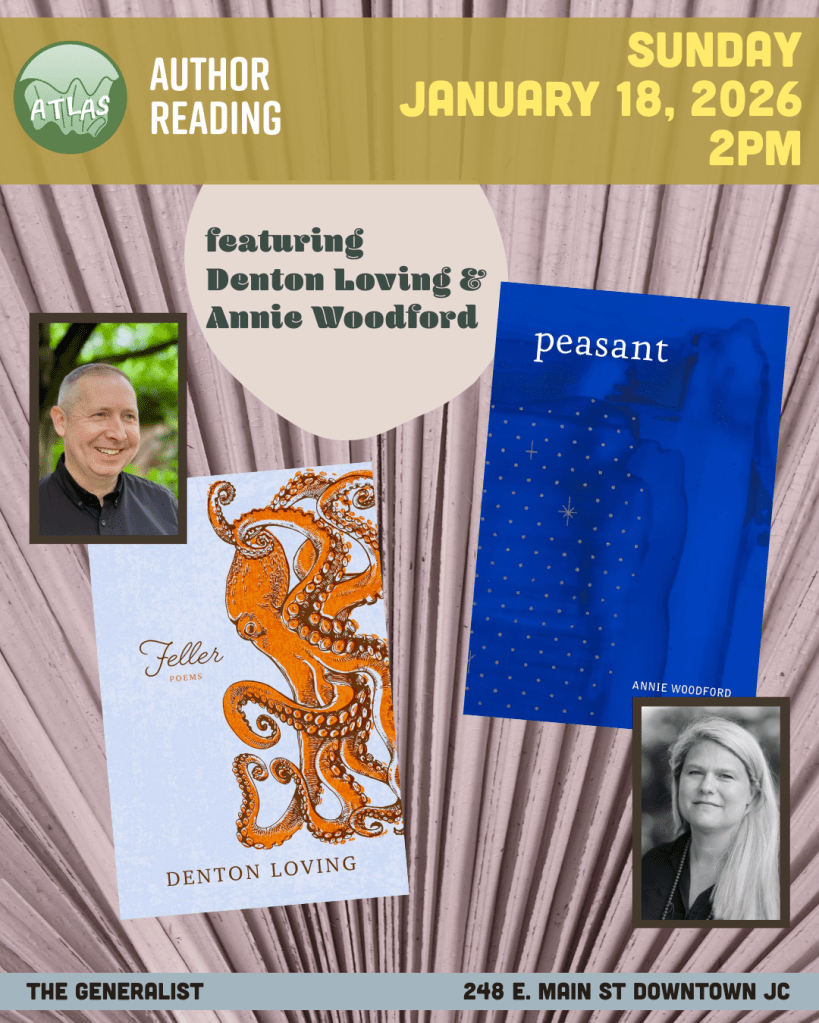

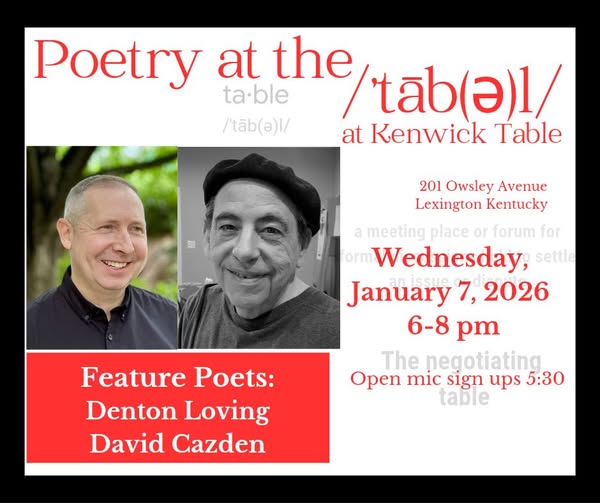

In case you missed it… I have a new book of poems called Feller that will be published on August 5th. I’ve been making the rounds to talk about the book and the general state of poetry. See my recent conversations with Emily Mohn-Slate in her “Beginner’s Mind” Series and with Greg Lehman in Episode 4 of Moon Beams. And for a limited time, pre-order Feller and get a 25% discount through Tertulia. Just enter the code FELLER at checkout.

If you’re not already receiving these posts directly to your inbox, please subscribe.