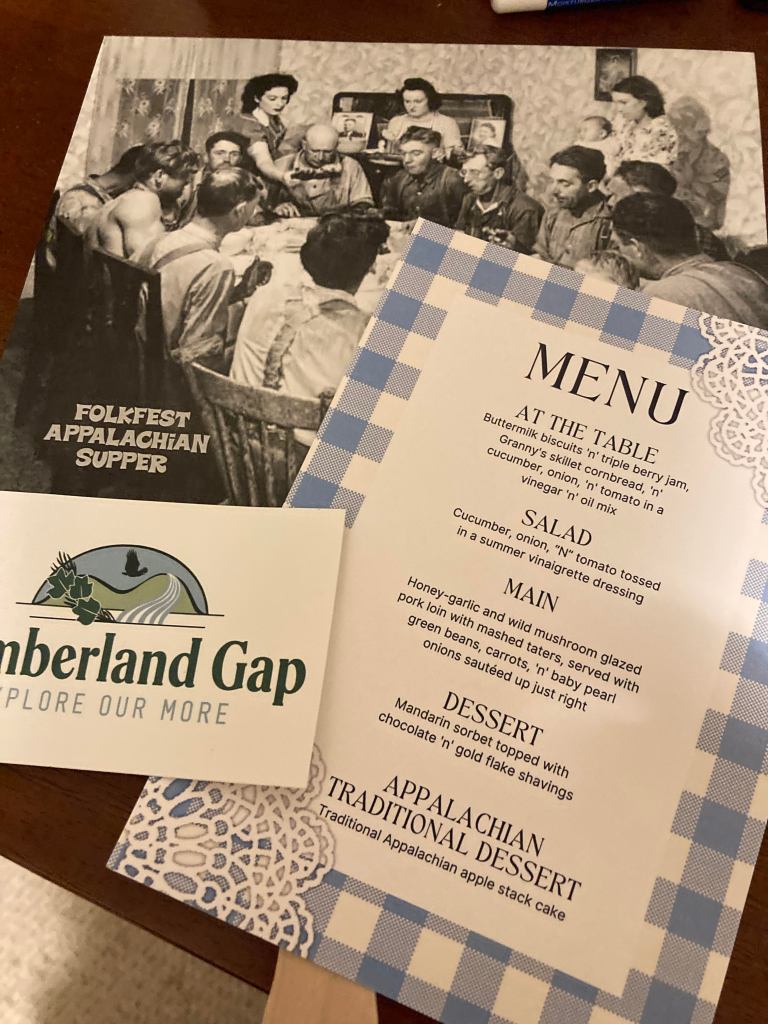

Last night, I was given the opportunity to read at the Folkfest Appalachian Supper in Cumberland Gap, Tennessee. This annual event to celebrate local and traditional foods is part of the city’s larger Folkfest weekend, which was re-introduced a few years ago by a citizen’s group called Guardians of the Gap. For my part in the event, I revisited a short essay I’d written several years ago about how I learned to raise a garden and how much my family has always loved fried corn. Here’s the essay and few pictures from last night’s farm-to-table dinner on the lawn. I hope that apple stack cake doesn’t make you too hungry.

There is a unique joy that comes from watching a seed emerge from the earth. In such a short amount of time, a kernel of corn, for example, grows from a tender green blade to a stalk that is taller than a person. In between these stages, if the rains have come at the right times (not too little but also not too much) and if the bugs and blackbirds haven’t eaten it all first, there are ears of delicious corn.

When I was growing up, my parents always raised a garden, and I was taught how to pull onions, cut cabbage heads, dig potatoes, husk corn, and pick everything that can be picked. It was important, especially to my dad, that I knew how to grow things, where food came from and that it involved hard work.

Six months after I graduated from college, my dad suffered a stroke. The doctors didn’t immediately think he would survive. And when he did survive, he was completely paralyzed on his left side. After weeks in a hospital and a rehabilitation facility, he finally came home, but everything in our lives was different after the stroke. That included the significance of the garden. All that winter and spring, as my dad endured daily physical and occupational therapy sessions, he talked about getting the ground ready to plant, and I became determined he would have his garden as usual.

My dad regained sensation and mobility. Only his left leg remained partially paralyzed, and he was fitted with a brace that kept his ankle from buckling under his own weight. He gradually was able to walk farther distances. But before he was strong enough to pull the starter cord on his old tiller, I would start it for him and shadow him as he guided the machine down a row. At first, it was all he could do to make it back to his starting place and then to his lawn chair under our crab apple tree. It exhausted him, but it was some of his most motivating physical therapy.

When my dad couldn’t be the gardener he wanted to be, he became a gardening coach, urging me to chop away the ever-persistent chickweed, to pull the dirt away from the onions and toward the potatoes. He instructed me until I was sick of the entire idea of gardening. I would sometimes quit out of frustration or maybe out of sheer resentment. I was sure I would never master this particular art, and I was frustrated at the amount of time the garden was taking away from what I wanted to do. But I always came back to it.

For almost a decade after that, I helped my parents raise their garden. While other jobs seemed to be expected of me, gardening was the one task my dad was verbally appreciative of. It made him happy to wake up in the morning, look out his kitchen window and see clean rows of young plants growing bigger, taller, thicker, stronger. I also learned to more fully appreciate the complimentary beauty of fresh green growth against the garden’s rich brown dirt. When the spring nights are still cool, the onion sets are slow to straighten and turn green. As the days grow warmer, the tiny lettuce seeds grow into a thick, luscious bed. When it’s finally warm enough to plant the beans, they sprout so fast, it can only be described as a miracle. The more involved I became with growing the garden, the more satisfied and grateful I felt for being a small part of that miracle.

In my family, the most anticipated meal of the year was always the day the first corn came in. We love it any way it can be cooked—boiled, baked or grilled, but to us, the greatest delicacy is fried corn. We cut it off, slow simmer it in butter and milk, and eat it with biscuits hot out of the oven. We’re not even too picky about the biscuits, as long as they exist. Fried corn is the star of this meal. There’s only a certain window in the year when fried corn comes. This delicacy can never be exactly duplicated with frozen or canned corn. You have to have fresh corn, and even fresh corn from the farmer’s market is not quite the same as corn straight out of your own garden.

We are in such a hurry to eat it that we are sometimes careless if a strand of silk makes it to the pan or even the plate. Fried corn is the most tangible reward for all the tilling, hoeing, weeding, watering, waiting and praying that is required in the previous two months. As much as the taste on our tongues is the satisfaction in our bones that all our hard work was worth it. We planted a row of seeds and had faith a meal would be delivered from it sometime later.

Witnessing the production of my own food—brought forth by my own hard work—changed my relationship with my dad who has been gone for almost eight years now. It changed my perspective on food and health, and on how I want to live my life. It changed the way I think about the lives of the people around me.

In the second chapter of My Antonia, Willa Cather writes about Jim Burden’s first visit to his grandmother’s garden. The well-preserved garden, full of flowers and vegetables, assures him that humans, when they die, “become part of something entire, whether it is sun and air, or goodness and knowledge. At any rate, that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great.” Every time I plant a seed, I feel connected to my dad. I feel connected to my ancestors and to all the people who turned the earth before me.

In case you missed it… check out my introduction for the launch of Darnell Arnoult’s new book of poems, Incantations.

~

If you’re not already receiving these posts directly to your inbox, please subscribe.

Hello Denton,

Your essay about planting seeds and enjoying the results brought me back to my grandmother’s kitchen table. My mother and I lived with those grandparents during World War II while my father was overseas. I’ve been writing about these and other members of my family in my two novels, Beyond Monongah and now Hardship and Hope, which just went live on Amazon. I don’t know if you’ve ever attended the Appalachian Writers Workshop in Hindman, Kentucky, but it has helped me immensely in keeping at the writing process year after year. I’m glad to be on your mailing list.

Thanks,

Judith Hoover

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing this! And congrats on your new book! Wonderful news!

LikeLike

Thanks. It’s a thrill to see it out there on Amazon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is such a beautiful essay. Thanks Denton!

I hope all is well,

Joanne

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

oh my ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Denton, what a beautiful piece. I relate. Dad gardened until he died in 1999. He mostly did it all himself, but when he had a joiner, they could learn 15 hours’ college credit worth, and witness wisdom, and joy and devotion. I wish you had read this last year, when Anne did stories, and I sang and played and had an historically good time. I hope to see you again before too awful long. How do you write roastinear— roast near? 😍

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I had been there last year to see and hear you all. I’d give a lot to hear one of those sermons you used to give, maybe about the goodness of gardens and fried corn!

LikeLike

This is great Denton. I think I commented on your blog but I am never sure. I love the images and the corn!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Lovely essay friend! Borders and miles may divide us, but we are united in our love of sweet corn, eaten on the same day it’s picked. Beings a northern, I’ve never tried your fried corn and biscuits. Up here, we keep it simple, boiled and slathered with butter and salt, despite our choking up hearts. It’s lovely to hear about your connection with your dad via bean and sprout, soil and hard-work. I hope to see your garden one day soon. xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Looking forward to your someday visit!

LikeLike

Hey Denton. I love this essay! We’re in the air between Atlanta and Paris with wi-fi, not as close to the earth! My dad’s mother would love you. She had a PhD in gardening and common sense. The essay says as much about you as your dad, and I’m a fan! I want to eat some fried corn. Delta just brought our dinner. 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Terry! Safe travels!

LikeLike

Thanks for posting your essay/reading. I totally identify with your satisfaction in growing your own food, and I’m happy it was your father—as it was mine—who taught you not only the basics of gardening but to love and appreciate the entire process from seed to a table filled with beautiful, delicious food.

The Folkfest sounds like a wonderful event.

Connie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Connie!

LikeLike

I love this. It’s wonderful. I’m not sure how I missed it in my emails. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person