I can’t exactly remember the first time I met Patti Frye Meredith. I definitely have memories of her at one of the early Mountain Heritage Literary Festivals making people laugh and playing music late at night. One thing I know for certain is that Patti can make anyone laugh. That’s true whether you’re fortunate enough to sit down and share a meal with her, or whether you’re reading her beautiful new novel, South of Heaven, a multi-generation narrative set in Carthage, a small town in the Sandhills of North Carolina. At the center of the novel are two sisters, Fern and Leona. Both have secrets they are keeping from each other and from the world. There’s also Fern’s son Dean who, as Fern says, doesn’t have any secrets. South of Heaven is a meaningful exploration of how the things we try to keep bottled up complicate relationships. The novel is deeply Southern, completely universal and wonderfully fun to read.

DL: South of Heaven centers on the McQueen family, and it’s set in the late 1990’s, a time not so long ago but a time that feels infinitely different in hindsight. Do you have any advice for other writers writing about the recent past?

PM: When Dean first “talked to me in my head,” he told me his dad was MIA in Vietnam, and how as a child he pretended to find his daddy in the overgrown bamboo patch in his backyard.

I wrote the book from that one scene. I knew Dean was in his early 20’s, and that his father went missing at the very end of the war. That’s why I set the novel in 1998. After I got into it, other 1998 occurrences came into play like the Clinton/Lewinsky drama. There’s a lot in the book about the lengths we will go to avoid the truth, so that worked.

Early readers suggested that I move the story up in time, to make it more contemporary, to use the Iraq War instead of the Vietnam War and put it in present tense. I tried, but I couldn’t make it work. By that time, too, I felt like I knew Fern and Leona very well, and I realized they wouldn’t be the same people if they hadn’t grown up like they did in the sixties.

There are pitfalls. It’s not historic, and it’s not contemporary. The characters are just modern enough for readers to wonder, “Why would they think that?” or “Why would they do that?” It’s embarrassing, but I had to do research to remember if everyone had cell phones in 1998, or if fax machines were still a thing. We’ve seen a lot of change in twenty-four years, and it’s amazing how quickly we forget recent history.

DL: I loved reading the “Backstory” on your website about your job at University of North Carolina Public Television, and how you met so many writers there. The authors you mention (Lee Smith, Doris Betts, Reynolds Price, Fred Chappell) all come from the Southern tradition, and South of Heaven feels like a very Southern novel. How natural was it for you to write in that tradition?

PM: Like so many others, reading Eudora Welty, Elizabeth Spencer, Lee Smith, Jill McCorkle, Tim McLaurin, and so on and so on, showed me that stories set in small towns were okay to write.

I grew up in Galax, Virginia, population around 6,000. So, it was natural to stick to the world I knew. Thinking about it, I’ve now lived in Memphis and Chattanooga, Tennessee, Huntsville, Alabama, Durham and Charlotte, North Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Cities large and small, but with the same southern sensibilities. (Or maybe I think all those places have the same southern sensibilities because “wherever you go, there you are”!)

DL: Did you feel any pressure to “live up” to the works of those writers you admired so much?

PM: If I thought I had to live up to their work, I’d never write another word! Back when I first started writing, I didn’t know what I didn’t know, however, it didn’t take long to realize I was never going to be in the same league with the writers I admired most. I’d give anything to see the world and put that world on the page like Fred Chappell, but I don’t have his complexity or depth. That doesn’t mean I don’t love reading his work. But, even when you study the craft and learn what makes great literature, even when you can recognize it, it’s still not possible to re-engineer your brain to create it. Thank heavens. There should be only one Lee Smith, one Jill McCorkle, one Darnell Arnoult.

That’s not to say I don’t spend a lot of time being discouraged! But you have to write what you write, be who you are, I mean, you can’t fake your subconscious! We all have our own perspectives and experiences, and we’ve all drawn our own conclusions.

I’m hooked on the joy of writing. The discoveries, the occasional good sentence, exploring the minds of my imaginary people. Writing helps me understand what matters and it’s my way of expressing what strikes me—good and bad—about being human.

And, since I love a cliché, I’ll say, “It’s the journey, not the destination.” Chasing after the “secret” to good writing has led me to friends who absolutely make my whole life better. Having the opportunity to be with other writers is the best reason to write! Sorry for getting off on a tangent, but maybe that’s the southern tradition!

DL: How long did it take you to write South of Heaven? How many drafts did you go through?

PM: There’s no telling how many drafts I have. Dean’s voice came to me at Hindman Settlement School in 2005. I wrote the original draft in first person present tense. Then changed it to third person present tense for my MFA thesis at the University of Memphis in 2012. Then I wrote a draft in third person past tense. I was always changing something, adding, taking away. Starting over. We moved seven times in twenty-eight years for my husband’s job, so I had a lot of distractions (excuses) through the years.

When my husband retired and we moved back to North Carolina, I set up my little office and joined a weekly writer’s group. Then the pandemic hit. Everyone is different. I know there are many great writers with extremely busy lives, but for me, the stillness of the pandemic quarantine made it possible to devote the time I needed to work. No travel, no socializing. I don’t think I understood what it meant to really work until the pandemic. I discovered the long stretches of uninterrupted time helped keep the story together in my head, helped me play out the scenes I needed to make the story more cohesive. I think of it as bandwidth. Writing South of Heaven took a lot of bandwidth!

DL: Your novel is published by Mint Hill Books, an imprint of Main Street Rag which published my poetry collection, Crimes Against Birds. What was your experience like in finding a publisher?

PM: I can’t remember if I saw Main Street Rag’s call for novel chapters on social media or in Poets & Writers, but I had one of those “What the heck” moments and sent chapters. Months later, I got an e-mail saying they were interested in publishing the novel, and Scott Douglass sent a contract and a detailed explanation of how the process would go.

I had sent out query letters to agents off and on for years. (One agent had almost taken it years ago, but that fell through when the third reader in her office didn’t think they could sell it.) I knew South of Heaven wasn’t the kind of book that was getting the attention of traditional publishing, or the independent presses I was familiar with. It wasn’t full-blown literary, and it wasn’t quirky enough to be chick-lit.

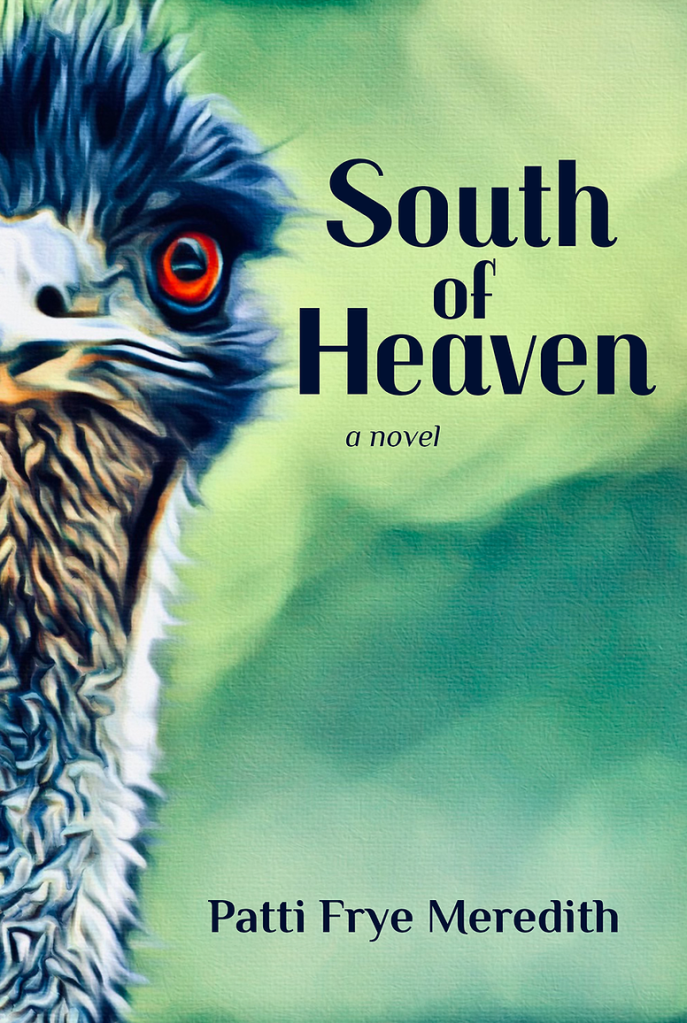

I didn’t think it was going to set the literary world on fire, but I wanted my imaginary people to live in a real book. So, I asked you, Sue Dunlap, and Darnell Arnoult to read it and tell me if I was about to embarrass myself, and you all said, “Do it.” So, I did. I fiddled with it after I got it back from you all, and I hired an editor to make sure I hadn’t added a lot more typos. Then I fiddled with it some more, and my niece, Becki Vasques, found my last snafus. We made it a family and friend affair! You and Darnell suggested I put an emu on the cover, and my husband, Lee, and I put it together (with Darnell on the phone). It’s been fun. Not “have lunch with your agent in New York City” fun, but better. A true labor of love. And I like that my North Carolina story is published by a North Carolina press. Scott Douglass does something very special with Main Street Rag. He publishes wonderful poetry and stories. I’ve gotten to know him and his wife and his dog, Harley, and I really appreciate the work he does.

DL: Do you have any advice for other writers ready to send their novel out?

PM: Don’t discount the small independent presses. We all appreciate independent bookstores. These presses deserve our appreciation, too.

Do ask yourself if you’re ready to be in the book marketing business, though, and the weird thing is part of that is selling not just the book but yourself. The great thing about the small press is, “You have a book to sell.” The scary thing about the small press is “YOU have a book to sell.” Just be honest with yourself about what you want to accomplish and why you’re doing it.

For me, the experience has been amazing because it has reminded me that I have the very best family and friends in the world. The support has been phenomenal. People I haven’t seen or talked to in ages bought my book after seeing my Facebook posts. Friends talk about my characters like they’re real people they care about. So, if I don’t sell another book, I’m very happy with the response South of Heaven has gotten.

CYNICAL ALERT!

The truth is, without Facebook, I wouldn’t have sold m(any) books. South of Heaven is in two bookstores, Chapters in Galax, my hometown, and McIntyre’s in Chapel Hill, where I live now. I’ve had one reading at McIntyre’s. I hired a publicist, and maybe there will be more readings, but maybe not. Even if I devote a lot of time to driving around, going to bookstores, taking them a book and a nice press kit, there’s no guarantee they’ll carry it. I have a couple of book club gatherings coming up. The bottom line is: It’s up to you to promote your book, to make yourself known. I believe even if you have an agent and a traditional press, they want you to have a “platform” meaning they want you to use your social media connections to publicize and sell your book.

DL: You’ve described South of Heaven as coming out “late in life.” We could argue about what that means, but I’m more interested in something else you said which is that having the novel out in the world helped clarify where and on what you want to focus your energies. Can you talk more about that?

PM: I know for sure I don’t want to be an author who dresses up and talks about writing. I want to be a writer who writes. I want to spend more time with my imaginary people and less time telling real people why they ought to like my book! Ha! I recently got together with a group of my writing friends, and afterwards I realized all we’d talked about was how close each of us were to having finished products to try to get published. Like there was some big door we were all clamoring to walk through to get to a different, more perfect life. I want to spend more time talking about ideas, or break-through moments, or what we’ve discovered about the craft. I don’t want my energy focused on end-products. I want to focus on better writing and storytelling.

DL: What are you working on now?

PM: Not much. I’m caught up doing what I think I ought to be doing to sell books. It’s uncomfortable and not much fun. I did have a little “conversation” with one of the characters in South of Heaven the other day. So, I wrote that down.

* * *

Find out more about Patti on her website, and don’t forget to order South of Heaven, now available from the Main Street Rag Bookstore. Coming soon, I’ll share my conversation with Tony Taddei about his debut story collection, The Sons of the Santorelli. Make sure you never miss a post by subscribing here: