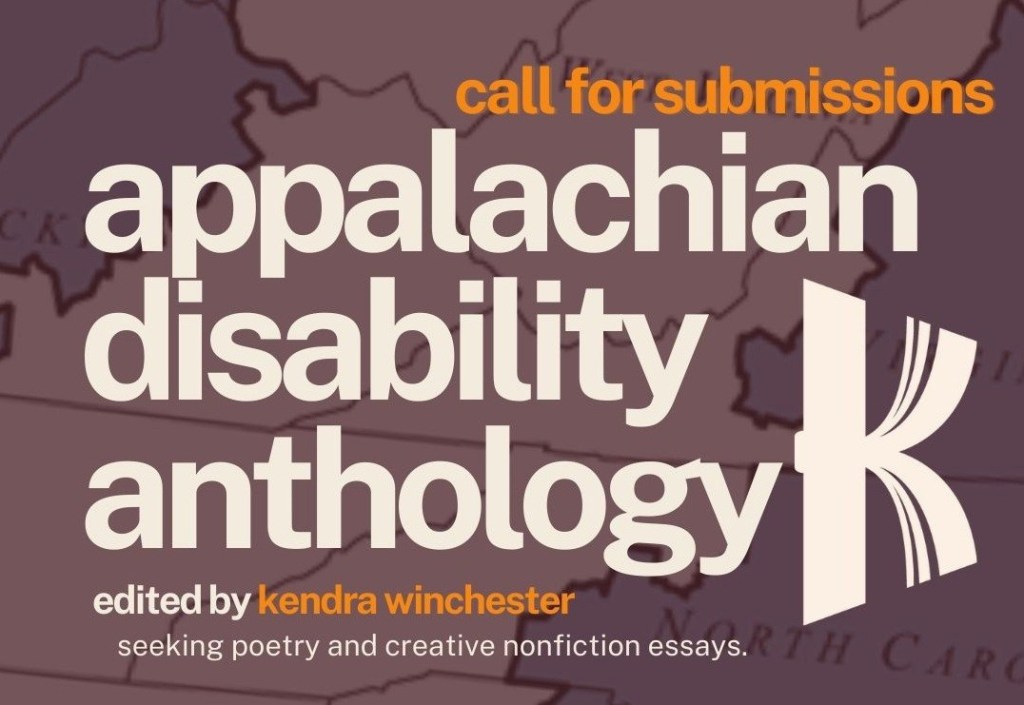

Many readers of this blog will be familiar with Kendra Winchester’s name from her work as the host of the popular Read Appalachia podcast, which celebrates Appalachian literature and writing. Kendra is also a Contributing Editor for Book Riot where she writes about audiobooks and disability literature. Kendra and I had a chance to spend some time together in person this past summer during the Appalachian Writers’ Workshop. One day while we were having lunch, Kendra started to tell me about her new project to compile and edit an anthology of work by disabled writers from Appalachia. The dining hall that day was so loud with conversation and laughter that we struggled to hear each other. So Kendra agreed to answer some questions over email about this anthology, which is actively accepting submissions.

DL: I was excited to learn that you will be editing an anthology of work by Appalachians writing about disability. How did the idea of this anthology form?

KW: Far too often, disabled people are treated like we’re invisible. When we are mentioned, we’re featured as inspirations, side characters, or burdens for the nondisabled people around us. Sometimes the very existence of our disability makes other people uncomfortable.

When I first read Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, I didn’t realize how rarely I saw my disabled self in books. Reading stories about people like me was something I never knew I needed. This led me to seeking out as many books by disabled authors as I could get my hands on. Little did I know that there was a whole disability community waiting for me. We have our own culture and history. People just have to realize that it’s there.

In the vein of Disability Visibility, I wanted to bring together Appalachian writers to tell their own stories of what it’s like being disabled in Appalachia. With poetry being such a vibrant tradition in the region, I also wanted to include poets, and my goodness, so many Appalachian poets have shown up in such a big way. My hope is that this anthology will be the first of many anthologies of disabled writers from the region sharing their work with the world. The more voices, the better.

Sometimes people ask me if their disability “counts,” but we’re using the big umbrella for disability. So anyone who is disabled, chronically ill, deaf, or neurodivergent is most welcome to submit.

DL: Do people with disabilities in our region face challenges that are unusual or different from other regions?

KW: Appalachia has higher rates of disability than the national average. Some disabled people have had to completely leave the region to seek treatment. Some disabled people can still live in the region but have to travel back and forth to urban centers to see specialists. And others are disabled because they worked in major Appalachian industries, such as coal mines and paper mills. Whatever our experience, we all have stories to tell.

DL: What genres are you seeking for this anthology, and how long should submissions be?

KW: I’m looking for creative nonfiction essays—around 2,500 – 3,000 words—that center the writer’s experience with living with disability in Appalachia. I’m also looking for poetry—3-5 poems—informed by personal experiences with disability in the region. I also welcome previously published work.

DL: Are you only looking for work from published, experienced writers?

KW: I’m looking for writers of all experience levels! The anthology includes experienced, prize-winning writers and people who have never had a published piece before.

DL: How can writers submit to your anthology, or reach out to you if they have questions?

KW: To submit their work or if anyone has questions, they can reach me at Kendra (at) readappalachia.com. I’m happy to answer any questions that they may have.

DL: When we were at the Appalachian Writers Workshop this past summer, you read a wonderful piece about growing up with a disability. Where can readers find that essay or any of your other recent work?

KW: Owning It: Our Disabled Childhoods in Our Own Words just came out in the U.S. this past August. It includes dozens of essays by disabled adults who were also disabled as kids. I was so honored to be included with writers like Ilya Kaminsky, Imani Barbarin, Ashley Harris Whaley, Rebekah Taussig, and Carly Findlay. I also write for Book Riot and have an occasional newsletter called.

Many thanks to Kendra Winchester for this important work and for answering my questions. You can find out more about Kendra and all of her projects by following her on Instagram or Twitter, or by subscribing to her occasional newsletter called Winchester Ave.

In case you missed it…Check out past conversations about writing and publishing with Melanie K. Hutsell, Zackary Vernon, and David Wesley Williams, whose new novel, Come Again No More, is out this week.

If you’re not already receiving these posts directly to your inbox, please subscribe.