Last week, I had the privilege to be part of the book launch for Darnell Arnoult’s new collection of poems, Incantations. This collection is a mesmerizing group of poems that celebrates language in unique but powerful ways. Many of the poems came out of a period of grief, but the poems are also celebratory and full of hope. They speak simultaneously to the personal and the political, addressing some of the most significant challenges of our times.

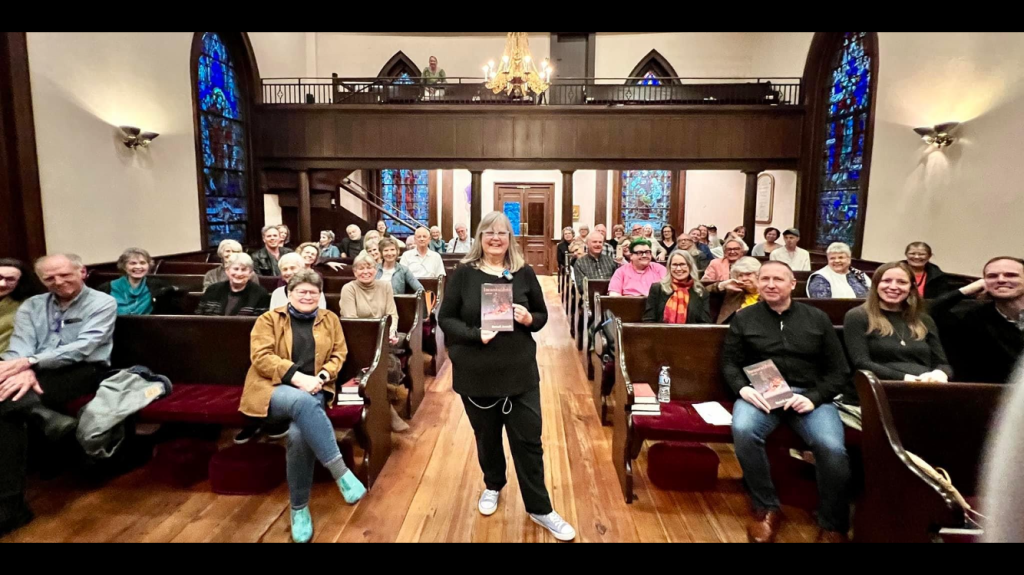

The launch took place in Hillsborough, North Carolina, at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church as part of their Faith and Arts Series. Darnell gave a beautiful reading of her new work. The church was filled, and Purple Crow Books sold all of their copies after the reading. Alison Weiner accompanied her on the piano. And I had double duty that night, first introducing Darnell and then following up with an on-stage discussion about her work. The on-stage discussion was especially fun, and I hope an audio recording of it will be available at a later time. Until then, I want to share my introduction. It was such an honor to be part of welcoming this new book into the world, as well as to celebrate my good friend. I may have also added a little good-natured ribbing.

Welcome, and thank you all for coming out tonight to celebrate our friend Darnell Arnoult and her newest collection of poems, Incantations!

If you are here tonight, there is a good chance that you already know Darnell. Before I get too personal, allow me to properly impress you with a few of Darnell’s professional accomplishments.

Darnell is the author of the novel Sufficient Grace, and two previous collections of poems: Galaxie Wagon and What Travels With Us, and she has published stories, poems and essays in a variety of journals and anthologies.

She is the recipient of the Southern Indie Booksellers Alliance Poetry Book of the Year Award, the Weatherford Award for Appalachian Literature, the Thomas and Lillie D. Chaffin Award, and the Mary Frances Hobson Medal for Arts and Letters. In 2007 she was named Tennessee Writer of the Year by the Tennessee Writers Alliance. She holds degrees from The University of Memphis, North Carolina State University, and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

If you know Darnell, it’s likely because you have studied with Darnell, perhaps at the Table Rock Writers Workshop, the John C. Campbell Folk School, the Appalachian Writers Workshop, the Tennessee Mountain Writers annual conference, through Learning Events, the Mountain Heritage Literary Festival, or perhaps even as an undergraduate student from Lincoln Memorial University where Darnell served as Writer-in-Residence from 2010 to 2020.

Lincoln Memorial University is the place where Darnell’s and my lives began to intertwine. We co-directed the Mountain Heritage Literary Festival. And we also created and shared editing responsibilities for the literary journal drafthorse, a journal dedicated to writing about labor and occupation. Darnell and I worked together, often getting each other in and out of trouble, and we became wonderful friends in the process.

I cannot list all of the pieces of good fortune that have come to me because of Darnell, mostly because Darnell told me to do something—often something I didn’t want to do or didn’t have faith that I could do. There are too many of these instances to list, but I will tell you that when I decided to apply to MFA programs, Darnell decided I would go to Bennington College’s low residency program in Vermont. I, on the other hand, lacked the ability to imagine being accepted in that program. I didn’t even have any intention of trying. But if you know Darnell, you know that once she’s made up her mind, you might as well agree or get out of the way. It is no exaggeration to tell you that the only reason I applied to Bennington was to shut Darnell up. As she seemed to know in advance, my life changed in innumerable ways because of that program, all for the better.

Darnell is the person who has encouraged me the most as a writer and certainly as a poet. Darnell probably knows my poetry better than anyone, and she has probably influenced my poetry more than anyone. A lot of my early poems originated in workshops Darnell taught. She was the first person who thought I had enough poetry to form my first book, and she largely arranged the order of that book, which in itself was another incredible lesson in learning how to shape individual pieces into a larger narrative. She has seen so many first and early drafts that it’s a wonder she still opens my emails.

In the 10 years that Darnell taught at LMU and lived in Cumberland Gap, Tennessee, my life was richer, and a lot more exciting. In her absence, there are fewer people asking me if I have seen Darnell, if I have any idea where Darnell is, if I can find her, please, help, she’s not answering her phone, she never answers her phone! Why doesn’t she ever answer her phone? There are fewer reasons to rush to the emergency room. There are fewer visits from the fire department. In short, there is much less excitement, and my life is poorer for her absence.

To answer the question as to why Darnell rarely ever answers her phone, I can report that she may have turned the ringer off two days earlier and can’t find the phone, she may have left her phone at home or at someone else’s home, or any number of other places along the way, the battery may be dead, or more likely, she is just already on the other line with someone else who needs to talk to her just as badly as you may need to talk to her. The number of people who rely on Darnell is uncountable. The number of people whose lives have been enriched by Darnell is legion.

I would be remiss to not acknowledge that the 10 years in which Darnell lived in Cumberland Gap were not completely happy. For Darnell, I know that time period is framed by her husband William’s recurring illnesses, his battle with cancer, and his passing in 2020. The poems in Incantations were born from that grief. The deepest kinds of grief. Grief that comes, as she would describe, from worlds burning, from death that dances and glides, from widowhood with its slaughtered and emptied heart.

And yet, within these poems, Darnell also rejoices in the curative properties of language, how it can bewitch and rescue us from despair. When you look at the beautiful cover of Darnell’s new book, you will see an image of fire and light bursting into the darkness. As that image suggests, these poems tell us that there is salvation in the darkness. There is salvation in these poems that are also charms for remembrance, charms for protection and rebirth, and always charms for love, no matter how it may shift its shape.

Join me in welcoming Darnell to the stage as we celebrate her new collection of poems, Incantations.

~

You can read a sample of poems from Incantations online at Cutleaf. Or you can order a copy through Purple Crow Books, directly from Madville Publishing, from your own local bookstore or anywhere books are sold. (Photos courtesy of Donna Campbell and Kelly March.)

~

In case you missed it… check out my conversation with David Wesley Williams about his novel Everybody Knows.

~

If you’re not already receiving these posts directly to your inbox, please subscribe.