Recently my friend William Kelley Woolfitt sent me an essay he thought I should see: Alison Stine’s “On Poverty” at The Kenyon Review. This essay was a response to an essay by Claire Vaye Watkins’ called “On Pandering.” Watkins’ essay received a lot of attention in literary circles, and there were many responses. But Alison Stine’s response is the best I have seen, and I wish more people would read it.

Earlier this week, I railed about J. D. Vance’s ignorant and stumbling assessment of Appalachia, the Rust Belt and the wider world in his poorly named memoir Hillbilly Elegy. One of my chief complaints about the book is that Vance addresses shockingly little about class structures and dynamics. Stine says infinitely more in her short essay than Vance says in his entire book.

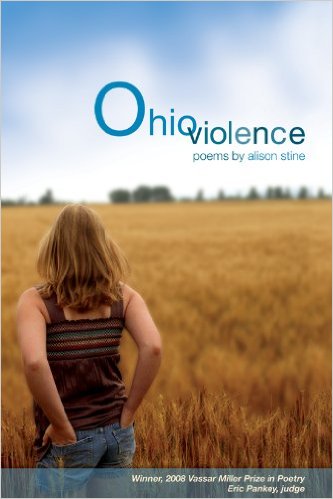

When I asked William to tell me more about Stine, he recommended her poetry collection, Ohio Violence, which I read this week and which I highly recommend. Ohio Violence was the 2008 winner of the Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry, and she’s written three books since it. Stine’s website links to a number of individual poems and essays, but here is one from Ohio Violence that I especially like. This poem, “When I Taught Mary to Eat Avacado,” is also found at Verse Daily. I hope you’ll enjoy her work as much as I do.

When I Taught Mary to Eat Avacado

She didn’t understand.

You couldn’t cut straight through with the big knife

because of the pit, or heart, or stone.

We gave it many names,

and when it was revealed, bone-shade,

heavy-bottomed, she wanted to keep it.

She washed it, and the skin

dried and crackled, lost shards. I taught her to salt

the pebbled rim, and dig with the tip

of a spoon, which is like a knife.

The flesh curl surprises, but it’s a taste you’ll miss.

When she stole the story I told then,

how the Aztecs locked up virgins

during the avocado harvest, how this was repeated

to others in her own language,

I knew we were bound to take

what we could from each other and go.

I didn’t tell her what the name

for avocado meant, its connection

to the male body, which she wanted no part of,

which I am now a part of.

Perhaps that is the end

of the story, his flesh in my mouth. Perhaps

the women were not locked up,

but went, willing.